Under The Cherry Moon

For D'angelo

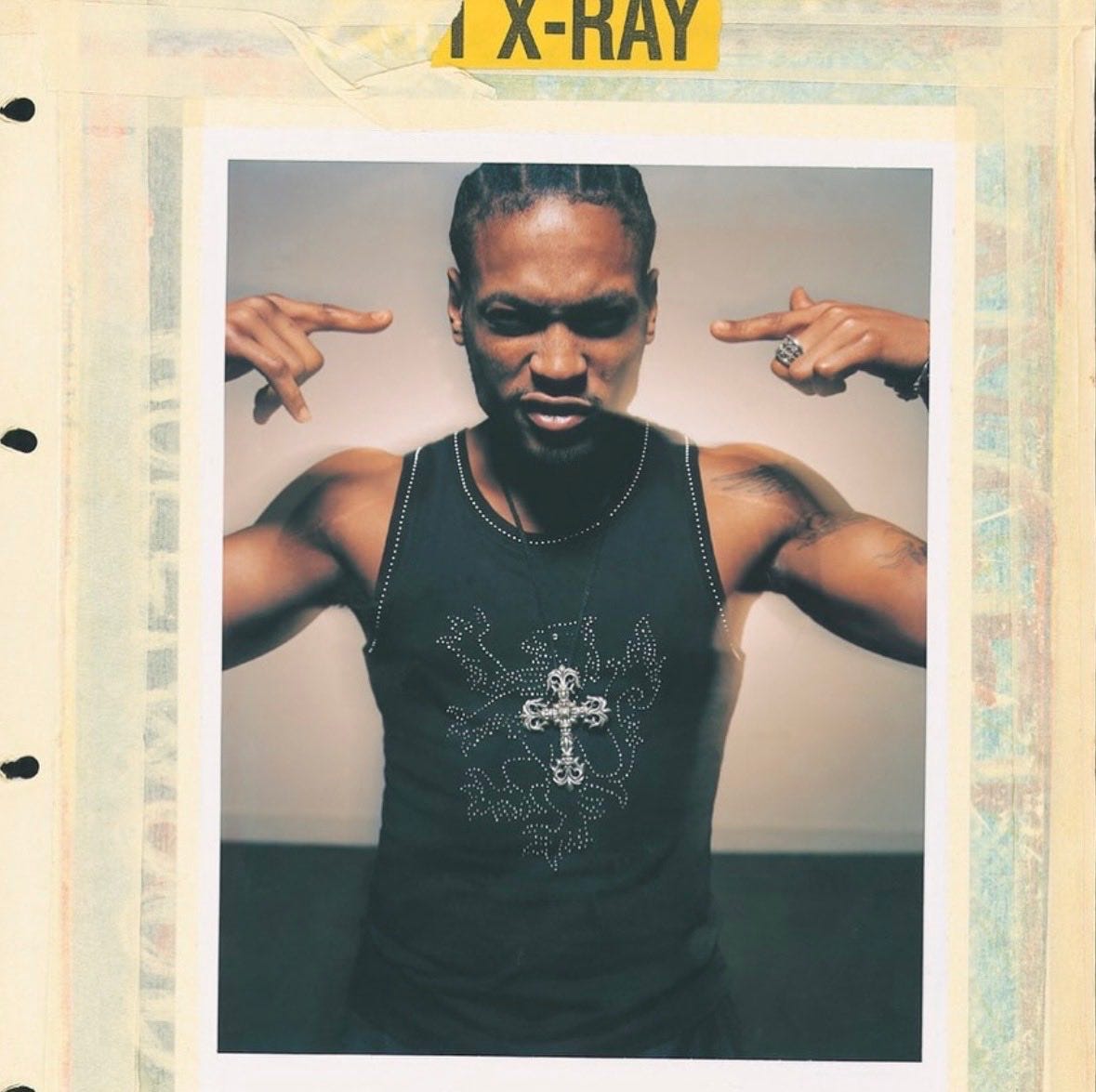

Since D’Angelo passed I keep thinking about 51, which seems like it should be one of those ages of transition where a saturn return or some other astrologically significant event briefly upends your life before settling you into the stability or rebellion of life on the other side of half a century. 51 is unceremonious and deeply painful to reconcile as an ending, especially for D’Angelo, who was one of those artists who seemed truly immortal, not by celebrity, but by the transcendental virtue of his music and my naive belief in karmic restitution for those who’ve been wronged. The day after he passed, trying and failing to think about something other than time, I watched Devil’s Pie, the 2019 documentary that follows D’Angelo’s tour preparation four years earlier. At seventeen, bright falsetto singing tomorrow, forget about tomorrow/won’t you give your heart today in his grandmother’s church, Michael Archer has already lived one-third of his life—Brown Sugar is on the near horizon, only slightly farther are the births of his three children, and all throughout the thread, questions of how to maintain the truly human and spiritual center of himself and his music in an industry that would rather cannibalize itself than prioritize an artist’s life over profit.

But while I am thinking about time in that way frightened young people tend to, what really stood out about Devil’s Pie was its fluid treatment of life’s time signature. D’Angelo’s younger self never disappears from the narrative in that way linear retellings of artists lives tend to begin with, dramatize, and then expunge the child or early artist. Every iteration of Michael Archer exists concurrently; the forty-one year old rockstar returning to the stage is also the Voodoo genius teetering on the edge of a cliff is also the seventeen year old Virginia church boy listening as his church testifies on his prodigious talent on the eve of his departure to pursue music professionally. The only thing that is true, all the time, is that life ends no matter how much we go about each day pretending and making tepid deals with God that it doesn’t happen to anyone we love. Like anyone who has suffered through mourning again and again, D’Angelo always seemed to hold that cosmic truth in his chest. It’s incredibly sad watching the documentary and reading his interviews and seeing the extent to which death loomed forebodingly in his mind and all around his life; deaths of family members and hometown friends, J Dilla gone at only 32, the dreams D’Angelo had throughout childhood of Marvin Gaye following his horrific murder1, as well the palpable dread of those who love him—including Questlove and tour manager Alan Leeds—who share in the documentary that they too, hold their breath for that eventual midnight call, D’Angelo’s eventual spiral past the point of return. That he’ll become another black musician immortalized by death is, throughout the 2000s and even after Black Messiah, an expectation.

It’s this phenomenon that really hurts, all the black people who learn of and experience death younger than they should have, and then spend the rest of life anticipating their own premature transition as if waiting for the sun to set in the evening. All the while time and age accumulating and the world confirming—in all the ways that it does—that their lives are, in fact, expendable. Every day since his passing, I’ve walked around my block listening to an album of his, and each time I so wish D’Angelo’s fears did not now read like prescience, but he had always understood his timing better than anyone else in the world: D-time, that languid pace of living and creating that meant lengthy periods between albums for an artist that refused to live by a label’s profit-hunting schedule.

At the end of James Baldwin’s 1957 short story ‘Sonny’s Blues’, the narrator, a cautious, purposefully square school teacher, accompanies his younger brother Sonny to a jazz club in the village. The vast ocean that separates the two brothers is mostly due to the elder’s compartmentalizing of his shame and what he witnesses and understands as the abject despair of living in poverty and the antiblack conditions of this country, and it’s this that makes him unwilling to empathize with his brother’s struggle with heroin addiction, unwilling to really hear Sonny’s music without the fearful avoidance of man trying to claw his way out of his origins. As the narrator sits in the audience and watches Sonny play piano on stage, he is made clergy to the band’s sermon; he is forced to witness: “All I know about music is that not many people ever really hear it…what we mainly hear, or hear corroborated, are personal private, vanishing evocations. But the man who creates the music is hearing something else, is dealing with the roar rising from the void and imposing order on it as it hits the air.” These pages are among the most moving and succinct words on the blues and that gulf between musician and listener that makes you feel so connected to the sound travelling to your ear and burrowing somewhere deeper, yet you’re still aware that what reaches you is dimensions removed from the phantasmagoria that the musician is working with.

I was reading this story just before the D’Angelo news broke and I read it again a few days later. Like Baldwin, D’Angelo was raised by a minister. Both men were generational, prodigious talents whose work rose above the tepidness of prodigy, both men never reached the repose of old age. Scenes from Sonny’s Blues play alongside Devil’s Pie in a mental side-by-side: Sonny is baptised mid-performance through the searching eyes and ears of the bassist Creole, who listens and speaks to him through their instruments/D’Angelo on stage at his piano, just before he launches into a boyish, sweet cover of “Que Sera, Sera”, looks back at his band with tearful eyes, before he’s embraced, one by one.

It is well past the one hour mark of Devil’s Pie that we finally hear the song. It is ‘Untitled’, performed in a rendition that is as sanctified as it is rock & roll. “It’s not the easiest thing to sing with tears in my eyes,” D’Angelo remarks during the outro to the crowd, smiling, out of breath, vulnerable in this moment where the depth of the song is felt doubly, beyond it’s devotional eroticism and far beyond the reductive fan mythology that its fetishistic video was the sole source of D’Angelo’s retreat from the public eye. What is it about the death of a public figure that encourages us to concretize simple narratives about their lives, especially for a man who built separation between the musician D’Angelo and the man Michael Archer in order to protect himself from the terror of fame and celebrity? For everything about D’Angelo that we can attempt to expunge and cipher through in death in an attempt to make his life story fit a familiar narrative, the very best and most sacred thing that he left us with is the music. I keep returning to ‘Betray My Heart’ because it feels like the artist’s mantra that stands at the center of so much of D’Angelo’s music. A spiritual successor to Voodoo’s ‘The Line’ to maintain integrity and selfhood in the art we make and share, as well the lives we live, and to devote oneself to capital-L LOVE in the most radical and uncompromising ways we can. You, my soul, can depend on me/You don’t ever have to fear/that my love is not sincere/I will never betray my heart.

https://www.gq.com/story/dangelo-gq-june-2012-interview

See also: D’Angelo’s tribute to Prince after his premature passing.

JAMES BALDWIN MENTION LETS GOOOO